Introduction

I remember as a small child being completely confused by the saying, “You can’t have your cake and eat it too!” as I couldn’t understand the point of having cake if one couldn’t eat it. I was adamant that it was possible to have it both ways, or when there were more than two ways, to combine the best of all options (like having French fries, ketchup and ice cream on the same plate!).

My rebellious tendencies growing up prepared me well for my work in teacher education and educational technology, guiding me to seek ways to mediate what I see all too often as a false dichotomy between choosing only one approach to teaching or one technology over another -- as if there are only two ways and as if we are allowed to pick only one. An example is the face-to-face vs. online teaching debate, with proponents of each arguing heatedly in favor of their preferred approach over the other. In this chapter I share how my own approaches to teaching have evolved as I have experimented with using a variety of different methods of teaching and using different educational technology tools all within one course – seeking to maximize the best of all possible worlds. My experience has culminated in my teaching a fully online course with a synchronous component (what I call a fully online hybrid model of teaching, or FOHM).

Since I first began teaching at the university level over two decades ago I have been an early adopter of emerging technologies. I have been fascinated by the possibilities each new tool has brought in helping me improve my teaching and my students’ learning. Inspired by the encouragement of different department heads over the years to try new approaches, and supported by our university’s academic technologists, I have learned not only how to use new and emerging technologies, but also how to make informed choices about which technologies and teaching approaches to use in different situations. The principle that has guided me throughout is that technology is never the point -- learning is.

In the early days of the Internet I learned the value of supplementing my teaching by creating course websites on which I provided links to online resources (including electronic copies of course materials). As these online resources increased in quality and with the emergence of Web 2.0 tools, my teaching evolved so that I had my students increasingly engage in online work as a core component of their preparation for our face-to-face classes. This meant that when they came to class we could spend more time on various types of active learning situations in which they applied and discussed what they learned outside of class. I also found myself using online tools, such as asynchronous discussion forums, wikis, and blogs to have students engage with one other after class to extend and deepen the conversations that they began in class.

When my university transitioned to using Moodle as a learning management system, I abandoned using my own course website as I found that Moodle provided an easy-to-use means of integrating many of the tools that I had previously used. I also changed the designation of my classes so they were listed as hybrid classes, with some seat time being replaced by online learning; this enabled me to expand the outside-of-class learning experiences that I had students do both in preparation for our class time and as a follow-up to class. This approach, now known as “the flipped classroom,” has become increasingly popular both at the pre-college and college level. In a flipped classroom, there is a shift in the role of both the instructor and the students. Instruction is “delivered” online outside of class, and class time becomes more like a workshop where students are actively engaged in hands on learning and in interacting with each other, while the teacher serves more as a facilitator (Educause Learning Initiative, 2012).

The catalyst for the next step in my teaching-with-technology journey came when I had to return to my home country, South Africa, in the middle of the semester due to a family medical emergency. Rather than cancelling class while I was gone, I decided to teach from South Africa to my students in the United States, using Adobe Connect. I had previously used Adobe Connect to participate in online meetings and also to attend virtual conferences. I had also used both Skype and Adobe Connect on a limited basis to enable students to join my classes from home when they were too ill to come to campus (especially helpful during the H1N1 flu outbreak). This gave me the confidence and background to attempt synchronous classes from across the ocean (and from a time zone seven hours ahead of Duluth MN!).

My plan was to have my students attend class on campus at their regularly scheduled class time and place, and I would join them online from South Africa; I would use Adobe Connect so that they would be able see and hear me via webcam, and also see the PowerPoint slides that I had uploaded. A colleague on campus helped by setting up the podium computer in the classroom, connected to a projector and speakers. Although my teaching was primarily lecture based, I still engaged students by having them work together in small groups and then report to me using the microphone on the podium computer. This worked adequately, and the students were excited by the experience of learning from a teacher who wasn’t even in the same time zone or country as them. If I had taught in this way for more than a couple of weeks I think the novelty would have quickly worn off because of my very limited repertoire of skills in teaching using Adobe Connect. What this experience did, however, both for my students and for me was help us to discover a whole new side of teaching that I hadn’t previously considered -- namely synchronous online teaching.

When my department head asked if I would consider teaching one of my two class sections of my Teaching in a Diverse Society class entirely online, I agreed, provided that I could make this a hybrid online class using what I called a fully online hybrid model (FOHM) – rather than the face-to-face hybrid model (FFHM) that I used for the second section of the class. What I proposed was that in the FOHM, the synchronous component would be in the form of an Adobe Connect online weekly class session, with the remainder of the course being fully online with students accessing learning resources and engaging asynchronously with each other using a variety of tools posted on my Moodle course site. The synchronous session would be offered outside of the usual class schedule times, thus enabling students to take day and evening classes and also attend to family or work responsibilities before coming to class. Based on input from students I scheduled the synchronous class to run from 8:15 - 9:30 p.m. on Monday evenings. This time was advertised in the class schedule so that students would know when they signed up for the class that it was fully online but had a required synchronous component.

Design of the Moodle course site

The Moodle course site was laid out so that students could see exactly what was expected each week of the semester. The first week they were assigned different tasks to help them to learn their way around the course site. They were also required to engage in a variety of asynchronous activities designed to help them get to know one another, to build a sense of community, and to learn to use some of the key tools on the course site. During this first week I analyzed their responses to survey questions and their self-introductions (in their first Moodle online forum). I used what I learned about the students to put them into heterogeneous groups for upcoming synchronous and asynchronous discussions and online group activities. They stayed in these same groups for the first half of the semester, and then a switched the groups for the second half.

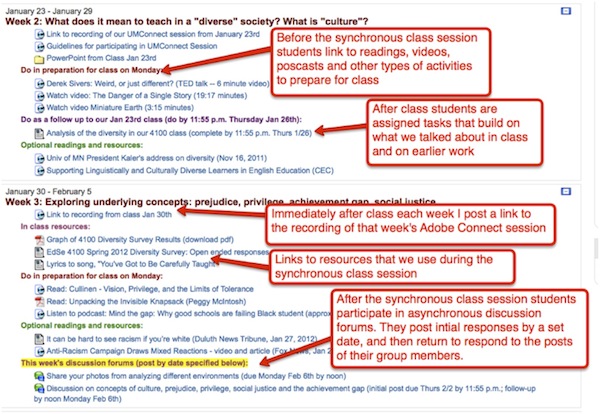

The Moodle site was set up so that there was a separate section for each week of the course. Each section provided the following:

- What students should to do in preparation for the weekly synchronous class session: Required tasks varied each week, but typically included a combination of readings, watching online videos, listening to podcasts, taking part in online simulations, and reporting on observations or field-based activities at the students’ practicum sites (in K-12 schools).

- Optional resources (for use both before and after the class session for enrichment)

- A link for students to access the synchronous Adobe Connect class session at the designated time. I recorded these weekly synchronous class sessions, and immediately after class I deleted the link to that week’s class session and replaced it with a link to the recording of the class so that students could watch it later (for review or if they missed the class).

- Follow-up tasks to be completed after the synchronous session. These included asynchronous discussion forums in which I asked students to build on what we did during the class session as well as to synthesize what they had learned from their practicum, readings/viewing/listening, and their own personal experiences.

Figure 1. The screen shot below shows two of the weekly sections of the Moodle site with annotations describing key elements of the course:

Design of the synchronous class sessions

In addition to being very intentional about building community and creating trust among the students and with me through the Moodle site activities, I also had to be sure to develop their skills and confidence in using the synchronous online tools in Adobe Connect. To do this I created detailed guidelines with screen shots showing students how to access Adobe Connect, what each of the components is and what it does, how to respond in chat forums and polls, and how to use the emoticon tools to engage non-verbally in class (e.g. raising their hands, indicating agreement or disagreement, applauding, laughing, asking me to speed up or slow down, and letting others and me know if they had stepped away from their computer).

During the first synchronous class session I guided students in learning how to use each of the Adobe Connect tools, being playful in doing so (e.g. having them applaud me, laugh at me, and telling me to speed up/slow down) so as to develop their confidence and skills before moving on to the course content. Then each week, at the start of every class, I would always do a sound check, asking them to raise their hand if they could hear me. If students didn’t raise their hands, I’d type in the chat window to ask them if they could hear. Thankfully students always could hear me - I didn’t ever have any technical problems - so I didn’t have to trouble shoot. However, I did have my phone number listed on the site so they could call me if they needed help.

At the start of class each week, when students logged into the session, they would see a PowerPoint slide in the main window (called a pod) indicating the topic of the class, the agenda, and a “Do Now” task asking students to respond in the chat window to a question designed to get them thinking about the topic as well as engaging with each other before the formal start of class. I would be logged in so students could see me in the video pod and hear my voice. Once class started, I would “freeze” the video so all that showed was a still picture, but they could still hear me (I did this as we found that the sound quality was better if I didn’t have the video running as well).

The purposes of the class sessions were for me to introduce new concepts, to frame the topic of the week and the tasks that students would do following class, and to have students begin to share their thoughts on that week’s topic. I used a variety of strategies to do this, including:

- Providing short explanations of ideas and concepts using PowerPoint slides as a visuals

- Having students respond to polls soliciting their opinions or seeking to find out what they understood about questions I posed

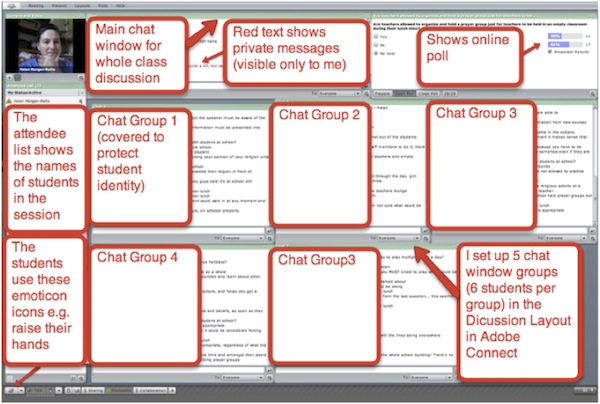

- Getting students to share their thoughts in response to questions I posed (e.g. in response to work they had done in preparation for class, to what I shared using the PowerPoint, or to the poll results). Sometimes I had students respond in the main chat window – similar to having a large group discussion with a whole class. Other times I would divide them up into discussion groups, with each group having their own chat window so they could respond within their group. They could still see the responses posted in other groups, but for the duration of the discussion I asked them just to follow and participate in their own group discussion. I would then ask them to pause and take a set amount of time (usually 5 minutes) to read other groups’ ideas. Then, using the main chat window, I’d ask for volunteers to share highlights of what they learned from reading other groups’ discussions. Alternatively I might have them return to their base groups and follow-up with observations from what they noticed other groups had discussed.

- As students typed responses in the chat windows, I would sometimes comment as the discussions evolved. For example, “Thanks Jane for getting the discussion started. You raise a key point about…. I wonder what others think about this – if you had the same reaction as Jane or if you interpreted this in another way?” or “I am seeing a number of people who found... while others have suggested… What about …?” I would encourage, redirect, paraphrase, and clarify as needed.

- I also used break-out sessions where students could see only their own group’s chat responses. Sometimes I had them use the whiteboard tool within break-out sessions to draw a concept map as a way of brainstorming ideas on a topic. When they returned from their break-out groups I would ask the group’s appointed reporter to summarize key points their group had raised.

Figure 2. The screen shot below shows the discussion layout of the Adobe Connect “classroom”:

- Findings and reflections on my experiences teaching using this fully online hybrid model:

- Students were very active in sharing ideas and questions with each other within their small-group chat windows. Although the nature of synchronous online chat limits the depth of these discussions, I found that these chats provided a valuable starting point to introduce a topic and give me the opportunity to clarify misconceptions. Students then followed up after class by engaging with their same small group members in much deeper, more thoughtful discussions within the asynchronous online discussion forums. The asynchronous discussions required them to synthesize what they had learned from their work in preparation for class, during the class, and as a result of follow-up tasks and practicum based assignments. This combination of synchronous and asynchronous discussion led to real depth of analysis, certainly equivalent to the quality of discussions from my face-to-face hybrid class.

- Interestingly, group work in chat groups enabled students to “hear” all voices in a way that is not possible in a face-to-face class discussion. In my face-to-face class (the other section of this same course), when I asked student to discuss the same kinds of questions with their groups, some students tended to dominate the discussion and others would not get a chance to share (or might be reluctant to do so). Online, however, students could all compose their thoughts at the same time after I posed the question. Usually there would be a minute or so where students would be typing and no posts would appear, and then responses would start appearing and the chat window would fill with ideas. I would give students time so that they could read and respond to each other’s comments. I would then ask students to take five minutes to read the discussions of all the other groups, looking for new insights, themes and commonalities. By contrast, in my other section of this same class, which met face-to-face, after small groups discussed, I would ask for a reporter from the group to share key points from her/his group. Even though groups took notes and decided what they wanted the reporter to share, inevitably the reporter tended to give her/his own interpretation of the group discussion. While the face-to-face class sharing allowed the reporter to elaborate in detail, this approach to group reporting is more of a “dipstick sampling” of ideas. Online, by contrast, all students (and I) could read everything that everyone had said, without our access to what others said being filtered through a group’s reporter. I could then also ask all students to do the analysis of themes or highlights.

- Student feedback has been overwhelmingly positive about the FOHM approach that I have used in my online classes. In spring 2012, 25 of the 29 students completed an anonymous online survey asking for feedback on the course; of these, 23 responded that they would take a course like this again. In the open-ended responses about the course they reported that they much preferred having a online hybrid class to an online class with no synchronous meetings. They said that they liked having to attend class synchronously each week, as this helped them to feel more engaged, to feel like a member of the class, to keep on track and not fall behind, and to be able to receive immediate help and feedback. They also like the flexibility of being able to attend class from anywhere and not having to come to campus, especially if they lived far away or had family or job responsibilities.

- I still prefer to teach face-to-face hybrid courses rather than fully online hybrid courses, because of the personal connection with students in a face-to-face environment. However, I have found that I really enjoyed the fully online class too, and felt that I got to know my students quite well through our online interactions. I would feel a real sense of loss if I taught only fully online, but am happy to have this be a part of my teaching load.

- The most important finding in both semesters of teaching this fully online hybrid model at the same time as teaching a second section using a face-to-face hybrid model was that, according to my analysis of student grades, there was no apparent difference between FOHM and FFHM class sections in student performance in all formal measures of student work (Moodle asynchronous discussion posts, group course projects, individual final course projects, and final exam scores). Additionally, student evaluations of the course and of the instructor on the end-of-semester official university evaluation form were very similar for both the FOHM and FFHM sections.

Advice on teaching synchronously online

- When setting up the Adobe Connect session, have a task displayed on a PowerPoint slide (as a “do now”) to get students engaged right away as soon as they log in (even before you formally start class). This directs them to begin posting their response to the Do Now in the chat window while they wait for class to start.

- Start class by using the video pod so students can see you as you speak, giving a more “live” feel in order to engage students. Then freeze the video so there is just a still picture of you but keep the audio going, as this improves the sound quality for the students. If the class includes a student who is deaf and who uses a sign language interpreter, then the video pod can be used to show the interpreter. Although this does work, the quality of the video is such that it isn’t easy to clearly see the interpreter’s hand movements.

- It is really important to have students actively engaged throughout the class, rather than merely sitting passively listening to you and watching PowerPoint slides. Students reported that it was hard for them to concentrate for long periods of time if they just listened to me and watched the slides. If you want to give a lecture, record it and post it in Moodle as a video or podcast; otherwise post lecture notes (in place of the lecture) prior to class. This way students can watch/listen/read these before class.

- When you do lecture, use the main screen with text slides to highlight key points and ideally also have engaging visuals. Change slides more often than you might normally in a face-to-face class so as to keep students’ attention and focus. Also engage them by asking them to respond to what you are saying and to what you are showing them on the screen.

- Ask students to respond often through the class period, for example by raising their (virtual) hands, by indicating agreement or disagreement, responding to poll questions, sharing comments or reactions in the chat window, or going to a break-out session to engage privately with their group without others seeing their discussion.

- Create small group chat windows (in the discussion layout), with groups pre-determined. Post group member’s names in each chat window so students know which group they are in. These small groups should be the same as the asynchronous discussion forum groups, so that students build trust in each other and also so they can continue to expand on their synchronous chat once they move to the asynchronous discussion after class. Change the groups every few weeks so students benefit from other perspectives.

- Have students use private messages if they want to ask each other questions and also if they want to tell you or ask you something in private. What I did when students sent me a private message or question was to share my response out loud to the class so long as it wasn’t something personal and if it was of value to the whole class to hear my response. I’d preface my response with, “I’m responding to a question raised as a private message about...” In a case like that I never indicated who sent the message. If my response needed to be confidential, then I would type a private response to the student. When I did this I would say to the class, “Just give me a moment here, I’m typing a private response to someone. While I’m doing this, you can....” (I’d give them a task to do).

- Although you can give students the option of using the microphone to share their responses orally, I found that this was not worth doing, as students had problems getting their microphone to work and we wasted valuable class time trouble shooting while the rest of the class had to wait. Having students participate by typing responses seemed to work well and enabled a more equitable level of participation among students (particularly with a class size of around 30 students). I still gave students the option of using their microphones if they indicated to me (in the survey that I give out in the first week of class) that they would have difficulties for any reason in being able to type responses in the chat window.

- It is very important to practice ahead of time and acquire a level of comfort in using Adobe Connect (or in whatever synchronous conferencing tool you choose for your class). It is better to use fewer of the Adobe Connect tools until you become comfortable both with the tools and with the pedagogy involved in teaching synchronously. It is more effective to keep it simple, rather than to try be too ambitious and become overwhelmed so that you aren’t able to have things work as they should. The good news is the technology in Adobe Connect usually works just fine. I have had hardly any problems as long as I have kept things simple and used only the tools that I am comfortable using. Usually the limiting factor is the instructor’s skill in using the technology and in synchronous online pedagogy, and not the technology itself.

Hopes for the future

Teaching using a fully online hybrid approach to my courses has opened a whole new world of teaching and learning possibilities for me, and has been a revitalizing experience. I realize that I have just begun to scratch the surface of what is possible when I let go of the notion that my students and I have to be in the same place and/or always together at the same time. When we see beyond the physical confines of brick-and-mortar classrooms and beyond the constraints of real time, so many more learning opportunities are possible. I think about the richness and depth that could be brought to learning experiences if we could have students in our classes not only from around our own country, but from around the world. We can also bring in guest speakers to our classes by phone, Skype, or other synchronous means from other places near and far. We can have students engage with these speakers in real time and have them post questions for the speakers on wikis or blogs, or engage with them in real time chat online. We can even have parts of courses – or even entire courses – taught by professors who live in another part of the country or world.

Also a wonderful dimension that is made possible is having the teacher be able to teach from locations other than on campus – whether that be from home, from travels around the country, or even from traveling around the world. For example, Donald Rallis, a geography professor from the University of Mary Washington in Virginia, teaches geography classes from around the world to his students in the USA. He takes his laptop and his web camera out onto the streets of Phnom Penh in Cambodia so that students in the synchronous component of his online course can see and hear what life is like there. They also look at this location in Google Earth and begin to pose questions about what intrigues them from all that they are seeing and hearing. Rallis teaches about the importance of location by pointing the camera out of his hotel window in Indonesia at the Strait of Malacca, so students can watch the shipping traffic on what is one of the most strategic shipping lanes in the world. He also makes short videos of scenes from this travels around the world and integrates these into his classes and also into his Regional Geography Blog (Rallis, 2011).

If we break down the walls of our classrooms and of our thinking even further, to go beyond the real world to the virtual world, even more becomes possible. In virtual worlds such as Second Life students can explore, learn about, and interact with others and the environment in simulations of real and imaginary places.

With the advances in technology the possibilities are endless, but what is so important is that we let go of seeing teaching and learning only in terms of the models used in the twentieth century. There is great value in the traditions of the past, but we can do so much more by also embracing emerging technologies to engage in truly transformative learning.

References

EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative (2012). 7 things you should know about flipped classrooms. ELI, February 7, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/Resources/7ThingsYouShouldKnowAboutFlipp/246344

Rallis, D.N. (2011, October 8). The strange tale of two rivers, and a lake. Regional GeogBlog. Retrieved from http://regionalgeography.org/101blog/?p=2533